History – Aisquith Street Meeting House

The Old Quaker Meeting house here in Old Town is the oldest religious building in the city, built in 1781. A number of influential Baltimore Quakers worshiped at the Aisquith Street Meetinghouse, among them Philip E. Thomas—first president of the B&O Railroad; Johns Hopkins; abolitionists Moses Sheppard (Sheppard Pratt) and Elisha Tyson and the Ellicott family. In 1926 the cemetery was moved to a new location in the county.

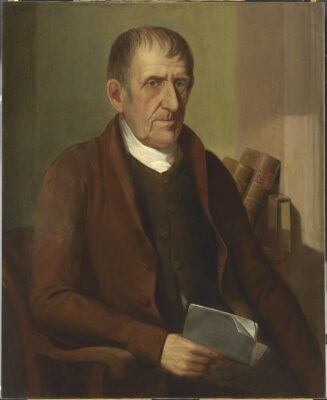

Elisha Tyson

The following, published in the Baltimore Sun in 2002, details about the life of Elisha Tyson, local abolitionist, who attended church at the meeting house in Old Town.

On Elisha Tyson

From the Baltimore Sun:

“Several years ago, Leroy Graham, a Baltimore historian and author of Baltimore: The 19th Century Black Capital , wrote a monograph on a little-remembered incident that predated the Amistad affair of 1839. The incident succeeded in bringing from his deathbed the intercession of Elisha Tyson, the Quaker-born abolitionist.

Tyson, who was descended from influential Germantown Quakers, had long been active in the commercial life of Philadelphia. He arrived in Harford County in 1772, and with a brother purchased Bond’s Water Mill, and entered the milling business.

An early Colonial millionaire, Tyson moved to Baltimore in 1781, where he became a well-known flour miller, merchant and trader. He was also a founder of the Savings Bank of Baltimore in 1818, and the Baltimore General Dispensary that provided free medical care to the poor.

However, Tyson never forgot his Quaker upbringing and the spirit of the Germantown Protest of 1688 that was the first public criticism and outcry against slavery in this country.

“To those Quakers, slavery was a gross sin against God and to be abandoned; enslaved Africans were to be helped, like everyone else,” observed The Evening Sun in 1983.

Tyson worked to frustrate the efforts of kidnappers who roamed the streets of Baltimore catching free or runaway slaves who were then sold back into slavery. He organized vigilante groups that battled the kidnappers who were known as the “Georgia men.”

In 1789, Tyson helped found the Maryland Society for the Abolition of Slavery, the state’s first abolitionist society. Also interested in the education of blacks, he began taking subscriptions in 1792 for the African Academy, which opened as the first permanent school for blacks in Baltimore in 1797.

By 1800, Tyson was operating a “safe house” on what was an underground railroad, making sure that runaway slaves made it safely across the border into Pennsylvania and into the hands of like-minded Quaker friends. He also saved thousands of kidnapped slaves through court suits. He shrugged off threats to burn his house or kill him, and continued fearlessly his work rescuing slaves.

Enraged one day at seeing agents of Austin Woolfolk, perhaps Baltimore’s most notorious slave dealer, dragging a black woman past his home, Tyson intervened and stopped them. Arriving at the scene, Woolfolk waved a pistol and swore to send Tyson to “hell for interfering with his property.”

Calmly, Tyson unbuttoned his shirt and exposed his chest. He invited the slave dealer to pull the trigger, telling him that he “was in hell already though he [Woolfolk] didn’t know it.”

As a member of the directors of the Maryland State Penitentiary that opened in 1811, Tyson made certain that the institution be operated without racial discrimination. He also was in the forefront of the movement to return blacks from Liberia to their homeland.

During the summer of 1822, the privateer Centilla, under the command of Capt. John Chase, formerly of Baltimore, had captured as a war prize on the high seas, the Brilliante Habanero, a Spanish slaver. Of 42 slaves onboard, 28 were sold in the West Indies, the remaining were impressed into Chase’s crew.

“According to both state and United States law, what Chase did was illegal; and upon discovering the true status of the fourteen, Tyson sought to gain their freedom,” writes Graham in his 1998 monograph. “Simultaneously, Tyson filed petition of freedom suits for the Africans which he and liked-minded abolitionist lawyers had done so many times before in Baltimore. It was Tyson’s reputation of 40 years of intense involvement in the anti-slavery movement that he could secure the quick legal cooperation of the chief judge of the Baltimore City Court to hear the Africans’ appeal.”

This time, the appeal was denied, and Tyson, though seriously ill, rushed to make a counter move. He enlisted the aid of Dr. Ely Ayres, an influential member of the American Colonization Society, and Robert G. Harper, a prominent politician and son-in-law of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the sole surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Changing his opinion, the judge ordered that the men be released, but not before Chase captured three, and the remaining 11 followed Ayres.

Baltimore had played a prominent role in encouraging the federal government to establish a site in Africa where slaves could be repatriated and returned to their homeland. But it was not until 1823 when the 11 slaves boarded the Fidelity, bound for Africa, its holds bulging with goods, tools, farming implements and household items purchased by Tyson.

Word reached Baltimore of the ship’s happy arrival in Africa.

“The most spectacular moment came as some of the men waded ashore and by chance their parents were on the beach,” wrote Graham. “Upon recognition of their children thought lost forever, the parents and children shed many tears of joy that overwhelmed all who were present.”

The news reached Tyson two days before his death. “After hearing the safe return of the group, Tyson supposedly stated that now he was content to die, which he did on February 16, 1824 at 75 years of age,” Graham wrote.

Tyson’s funeral was one of the largest ever held in the city.

Fittingly, several thousand blacks, grateful for his life’s work, accompanied Tyson to his grave.”